Researching climate change adaptation governance: a journey into rural Zimbabwe

As part of the LINCZ project, I spent a month in Zimbabwe talking with people about how their communities are adapting to climate change in their daily lives, and how they collaborate among the actors and organizations involved at the ward, village, and district levels.

Daily Research Activities

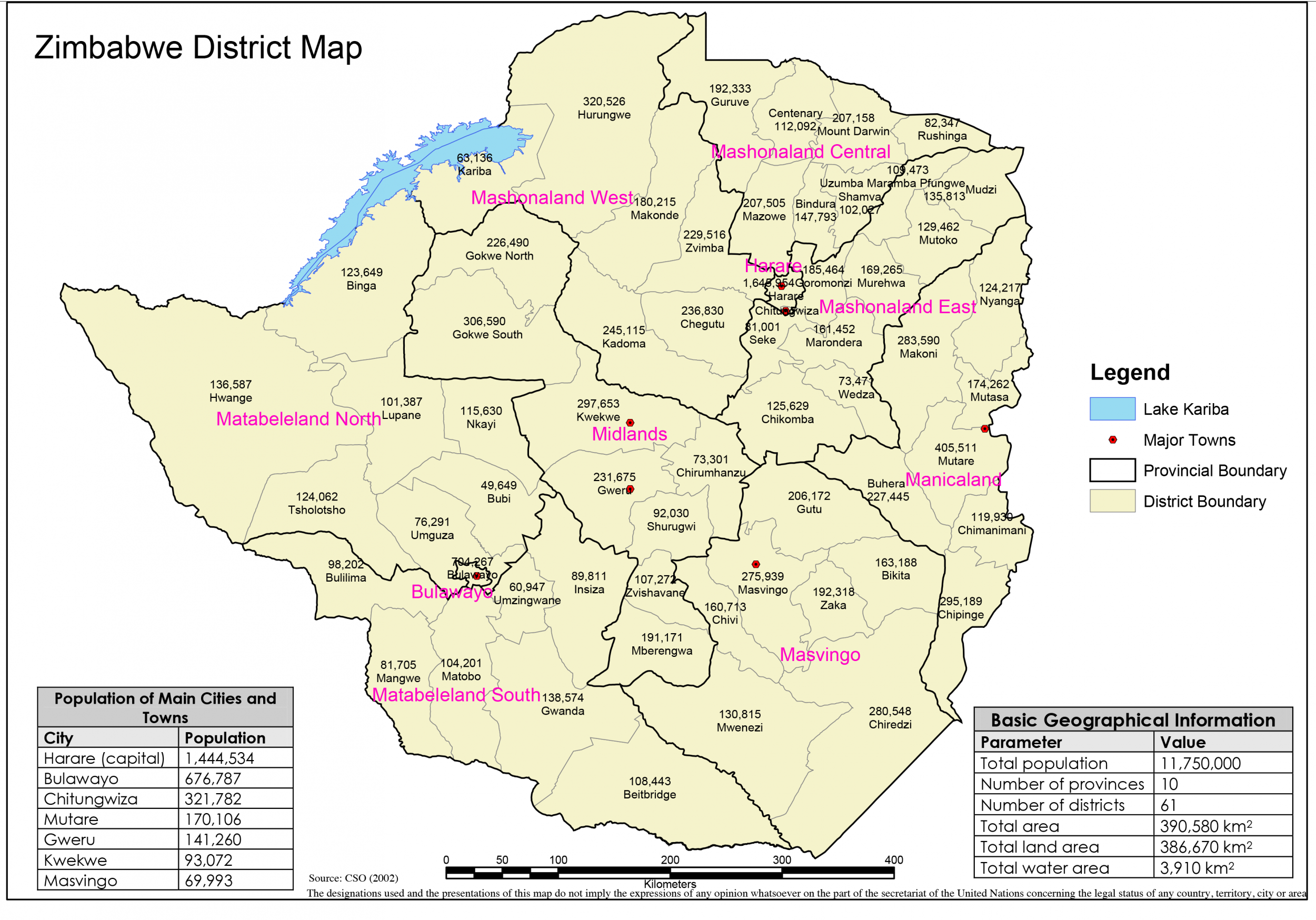

In June 2024, I met with colleagues from Mennonite Central Committee Zimbabwe's partners from Score Against Poverty and Brethren in Christ Compassionate and Development Services. Then, we visited communities in the Mwenezi District of Masvingo Province and the Gwanda District of Matabeleland South Province of Zimbabwe. There, we spoke with local stakeholders about the challenges and opportunities in responding to climate change in their communities.

We travelled over 2000 kilometers and spoke with over 30 people, who, because of their role in a community, have relevant experience and knowledge about climate change adaptation policies and by-laws, decision-making and implementing initiatives. We joined in the meetings of stakeholders and project staff and the activities of over 200 people. We also collected copies of and references to documents, including fifteen natural resource, environment and climate change policies at the national and district levels.

Challenges Encountered

With an ambitious schedule, we faced unforeseen changes in participants' availability (such as the well-attended funeral of a prominent community member), and the unpredictable pace of travel over rural roads, through construction zones, or behind transport truck convoys. The tremendous patience and flexibility of project staff and participants made it possible to shift plans and to minimize disruptions. A stint early on in my trip with traveler's diarrhea was resolved through treatment with a medicinal bark concoction, thanks to the traditional knowledge of a project partner staff person (and former Forest Commission Extension Officer).

Local Interactions and Culture

Collaborating with many people, we learned that climate change adaptation needs to bridge the past and present, to integrate time-tested traditional agricultural wisdom and conservation techniques along with new approaches. With patient close collaborators, I struggled to learn a few words in Shona and Ndebele, the main local languages in the communities I visited, and a couple of Xhangani and Sotho words too, in areas where these local languages are also used. Less adventuresome in my diet than I might have been, I still regularly enjoyed sadza (a staple maize meal starch) – roasted chicken, and chomolia (kale/collard greens), as well as once tasting the famed mopane worms.

Emerging Insights, Reflections and Takeaways

Zimbabwe's policy landscape clearly shows commitment to climate change adaptation, which is meaningful to local communities. Key informants mentioned the Environmental Management Act, the Forestry Act, the Natural Resources Act, and the Traditional Leaders Act. These are complemented by the Zimbabwe Climate Policy, the National Climate Change Response Strategy, and Zimbabwe Climate Change Gender Action Plan.

The tasks related to planning and implementing adaptation initiatives involve multiple actors at multiple levels, working to set and align priorities, which may have local, provincial, and national scope. Perhaps the main insight is: 'it's complicated.' Traditional, governmental and nongovernmental actors work side by side, to navigate the complexity and collaborate on initiatives such as agroecological farming, forest conservation, water management, landscape rehabilitation, artisanal bee-keeping, and improved fodder for livestock.

Future Directions

This research will continue to analyse how by-laws and policies influence ongoing collaboration through complexity by those living everyday with chronic and acute impacts of climate change in Zimbabwe. Ultimately, the project goals include supporting Zimbabweans as they navigate and help shape the decisions, design, and delivery of climate change adaptation initiatives from local to the national levels. Findings from this research visit will also shape my second research visit planned for Spring 2025. Then I will test learnings from largely grassroots and local community actors visited in June 2024 with provincial and national-level actors, stakeholders, and policymakers. This research will contribute further to the LINCZ Learning and Research Hub, complement and amplify work by colleagues from Canadian Mennonite University, NUST and the Bindura University of Science Education (BUSE) as part of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF).

Acknowledgments

Counting staff from MCC Zimbabwe, Score Against Poverty, Brethren in Christ Compassionate and Development Services, and faculty and students from the National University of Science and Technology, more than a dozen people were close colleagues during my trip. Among them, my daily companion deserves special mention, LINCZ Learning and Research Hub Coordinator (Zimbabwe) Bulisani Mlotshwa. Beyond these there were, seen and unseen, the staff of the same organizations, as well as the corresponding people at MCC Canada and CMU. The research participants and their staff, spouses, and peers gave generously and patiently of their time and energy. To all these all I offer my deepest gratitude for support, hospitality, encouragement, insight, and wisdom. Thank you. Tinotenda (Shona). Siyabonga (Ndebele).